The Happy, Hellish Journey of Starting a Distillery

We have zero plans to build and sell the distillery. We want to own and be a part of it for a very long time.

In 2022, Jane Bowie and Denny Potter left plum positions as head of blending and master distiller, respectively, at Maker’s Mark Distillery to launch their own brand, Potter Jane Distilling Co., in Springfield, Ky. Theirs wasn’t a move to source others’ whiskeys to bottle and badge as their own, they burned to build a distillery from the ground up.

Among some who questioned their sanity were Bowie and Potter themselves. They say hardly a day passes without wondering whether leaving Maker’s was the smartest idea. Their salaries were handsome, regular paying and bonus-incentivized, benefits their families liked. Such fretting is common for entrepreneurs, especially those whose jobs are coveted positions in a red-hot industry and anchored at the Red Wax brand.

BourbonBanter.com talked to them in August about the triumphs and tribulations of starting a distillery from nothing, the thrill of the new adventure, the nail biting that follows every check cut to a contractor, and the anticipation of seeing whiskey flow from still to barrel in January.

Denny Potter: A priority from the beginning was to be majority owners in the distillery. … We weren’t aware that (our eventual lender, Truist Bank), had been involved in the industry and had been looking to back a project like this. So, we talked to them and had some great conversations, but then we didn’t hear anything for a while.

Six weeks later, they wanted to have another meeting. In those six weeks, they did a ton of research, their due diligence on who we were and what we'd done in the industry. We never thought they would give us the amount of money they would ($50 million).

Jane Bowie: As they’re presenting their findings, at first we were too stupid to understand that they were loaning us the money. When I realized they were, I thought I was going to be sick. We weren’t jumping up and down all excited, it was kind of this feeling of, “Oh, we have to go do this now.”

… a generational business

Denny Potter: We have zero plans to build and sell the distillery. We want to own and be a part of it for a very long time. We’ve spent our whole careers working in generational operations and telling those stories of why that’s important. Those families … are still integral parts of those places, whether they’re Samuels, Noes, Beams or Shapiras. How cool would it be to be generation number one in this business and hand that down?

Jane Bowie: We never imagined being Pat (Heist) and Shane (Baker, who sold Wilderness Trail Distillery for an eventual $620 million). I think our future is our kids, a generational place where my daughter is arguing with Denny’s son.

We weren't born into this industry. We’re just kind-of expats who fell in love with it. I think it's one of those industries where you’re like a fish in water or you're just not. There’s not much in between. There are people who just get into it and love it and they can't imagine doing anything else.

… so what do you do?

Our roles here? That’s something I’m wondering about every day! It was easy to be in lockstep (at Maker’s) because things were established. This is different.

Denny Potter: I'm in the details, in the numbers. That’s what I enjoy because I’m naturally an introvert. Lock me in a room and let me do that. Jane’s outgoing. Her ability is to bring people along for the journey. On the relationship building side, say with contractors, she's incredible.

Jane Bowie: But I think our jobs will look a lot different in six months after we’re distilling. What we’re figuring out now is all the stuff we took for granted before, like corporate HR. We see making whiskey as the easy part.

Denny Potter: We're working on our employee handbook right right now, developing all these policies and figuring out vacations, what maternity leave is going to look like ... all that's new to us. And we still have to hire our team.

… even with millions, money’s tight

Jane Bowie: Though we have our loan to do this distillery, money is always an issue. It turns out we were good at spending others’ money before! Now that we’re responsible for it, we're like, “We can't afford that.” A trip for breakfast or lunch in Louisville is now a big deal.

We don't have a huge budget for fancy (analytical) equipment, and I'm going to miss all that. But the truth is the nose is still the best piece of equipment you’ve got.

Denny Potter: No GC (gas chromatograph) at the beginning, but sometime down the road for sure.

… should we have done this?

Denny Potter: When we look at all that’s left to do and what’s to come, it makes us a little anxious.

Jane Bowie: It does, for sure. Rob Samuels hired me when I was 25 years old, and it's the only industry job I’ve ever really had. So, there’s this fear of whether I’m good at anything else.

Denny Potter: We talk about imposter syndrome, that all this time we’ve been pumping ourselves up, hyping each other up and saying we’ll be really good at this. And then we start thinking, “This is going to be terrible. It’s going to be the worst whiskey in the world, with the world's worst packaging and worst sales pitch … .” We’re like, “What happened? We were so good working for somebody else!”

Jane Bowie: That’s when I look back and remember Maker’s was a beautiful place to work. It was where all my friends work, and the paycheck was regular, and I got to go to Japan twice a year! But the truth is if we weren't scared about this, that would probably be bad. This is serious. It’s big! But while we do believe in ourselves, we also live like it’s terrifying.

… details of distilling

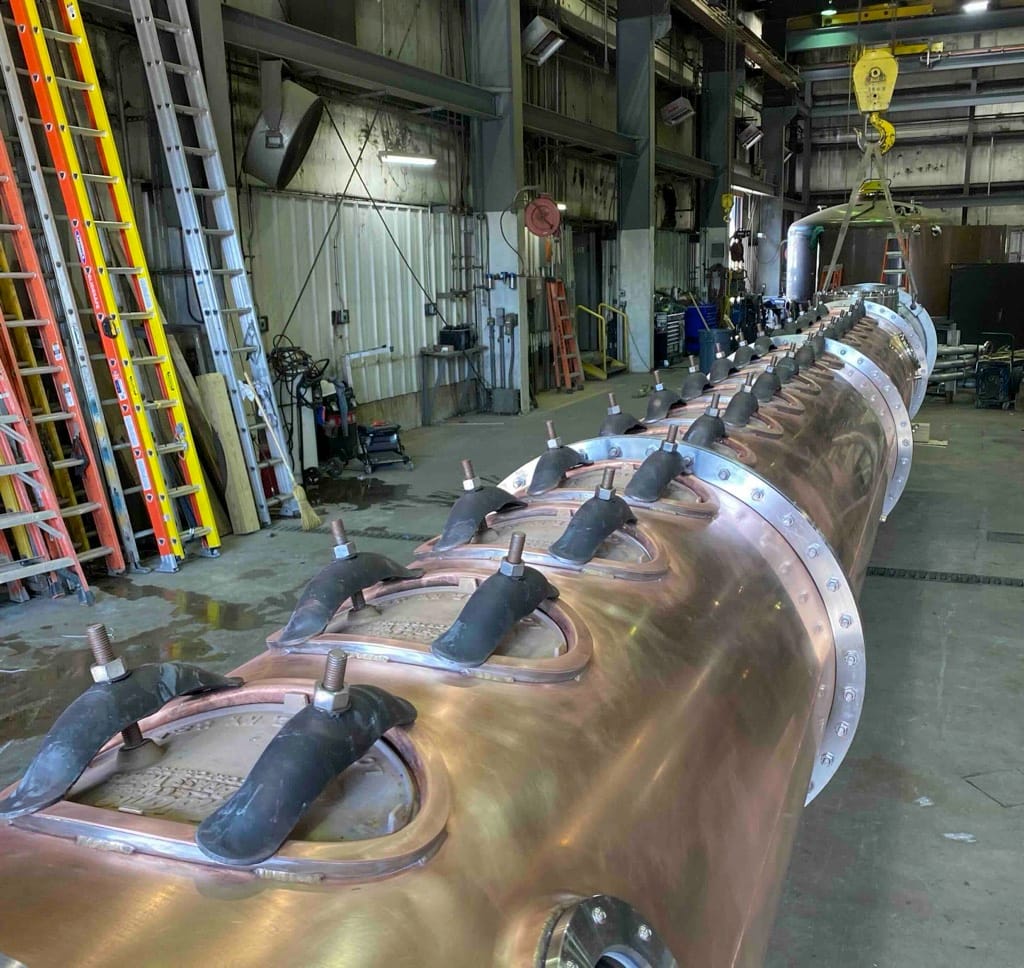

Denny Potter: We’re going to have a 36-inch column still … and we’ll eventually do somewhere around 2 million proof gallons a year. We could get that close to 3 million a year if we ran seven days a week

Jane Bowie: We’ll have ten 20,000-gallon open-top fermenters.

Denny Potter: At Maker’s all the fermenters were open top, and it was so easy to walk through the operation and assess a lot visually. And when you have closed-top fermenters, it’s a hell of a lot more work to open them up and close them all the time.

Jane Bowie: We will have two 10,000-gallon cookers versus one. That will give us the ability to cool the mash in the cooker … and do different things with lower-temperature fermentations.

Denny Potter: We’ll use a roller mill for our grain. They’re easier to work with than hammer mills and, frankly, hammer mills are loud.

Jane Bowie: A lot of people have strong opinions on which type of mill to use, but neither choice is better or worse. It’s just a preference.

We’ll have 24,000-barrel traditional rickhouses. The first will be ready by January. (They’ll have 14 total.)

Denny Potter: Buzick Construction will set up a sawmill here in October and build the rigging. What you can’t do is put (a rickhouse) up too fast and not have barrels to put inside them. Basically, your barrels are the support structure, so what you don't want to do is to build it and then not put barrels in it for a while.

After we clean the whole place, and I mean everything, which is a pain, we should be running water through the whole system right after New Year’s. By mid-January, we expect to be putting distillate into barrels.

Overall, this has been an incredibly fun process, the easiest construction process I’ve ever been through for sure. Part of that is because it’s a greenfield build. It’s not like the challenge of squeezing a new 66-inch column still next to two others like we did at Bernheim (Heaven Hill’s main distillery in Louisville, where Potter was master distiller). We got to start from scratch and lay it out in such a way that it flows smoothly from one end to the other. We're really pleased with the design.