The Embassy Series: A Journey Through the World’s Native Spirits

On May 4, 1964, the United States Congress passed legislation that we can all agree was a wise move: the designation of Bourbon Whiskey as a uniquely American product and our country’s native spirit.

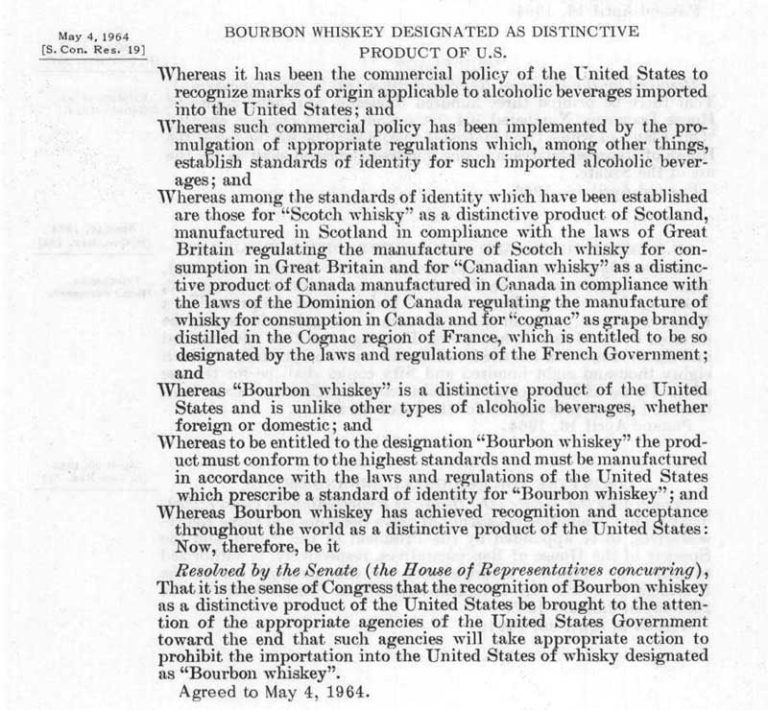

On May 4, 1964, the United States Congress passed legislation that we can all agree was a wise move: the designation of Bourbon Whiskey as a uniquely American product and our country’s native spirit. The Senate Concurrent Resolution 19 (“Bourbon Whiskey Designated as Distinctive Product of U.S.”) is perhaps the only bit of legislation passed over the past half-century that every one of us – regardless of political camp – can rally behind. The designation was undoubtedly rooted in protectionist trade policy and economic politics, but it is one that solidified a uniquely American tradition of making and aging corn whiskey, a native grain of the United States.

Regardless of which origin story you believe (Elijah Craig and the fire in the whiskey storehouse, or Jacob Spears’s ingenuity in Bourbon County), Bourbon has been produced in the U.S. – and notably Kentucky – for nearly two centuries. The popularity of corn whiskey grew from a simple fact: corn grew well in Kentucky and folks had a lot of it. As this corn liquor was shipped down the river to the Port of New Orleans, where it gained significant popularity on Bourbon Street (which many credit as the actual origin of the name) due to the more mellow characteristics the white liquor garnered from the barrels (a common storage container at the time) as they rolled down the Mississippi on a journey that could take the better part of a year. A happy accident perhaps, but one that changed the way we drink in America, as well as the economies of the country and the Bluegrass State (the industry garners close to $3B per year). (Source: Distilled Spirits Council of the United States)

Many stars aligned to yield us the Bourbon we know and love today, but many of the reasons were derived from geography. It only makes sense that the U.S. make a legal claim over this uncommon breed of liquor. However, Bourbon was not the first spirit – let alone whisk(e)y – to garner appellation status. As support for the designation, the resolution cites Scotch whisky, Canadian whisky, and cognac as other spirits that hold protection for “standards of identity.” These protections are essential, as they allow they unique industries to flourish and gain notoriety on a global scale. It would be rare to encounter someone who has not heard of Scotch, but what about the native spirits of other countries?

There is a wide world out there of lesser-known spirits that are just as deeply rooted in the histories and cultures of their homelands as Bourbon. In my upcoming series – “The Embassy Series: A Journey Through the World’s Native Spirits,” I will delve into the story of a new spirit each month, along with a brief history of its creation, its local cultural significance, a few tasting notes, and maybe a cocktail or two. Think of it as “Spirited Diplomacy.” The first installment will feature Chacha, the grappa-esque liquor from the wine-rich Republic of Georgia. Other months will feature spirits such as Cachaca from Brazil, Soju from Korea, Raki from Turkey, among many others.

Get your passports and glasses ready folks; we are in for an exciting – and boozy – ride!