Bottled In Bond: A Brief History

During your last visit to Ye Olde Liquor Store, you might have noticed a couple of bottom-shelf bottles sporting a fancy, old-script tag: “Bottled-in-Bond.” The bottle might claim that the whiskey is exceptional, full of heritage, made according to an old, forgotten tradition.

During your last visit to Ye Olde Liquor Store, you might have noticed a couple of bottom-shelf bottles sporting a fancy, old-script tag: “Bottled-in-Bond.” The bottle might claim that the whiskey is exceptional, full of heritage, made according to an old, forgotten tradition. Companies such as Heaven Hill, Barton, and Jim Beam have revitalized the century-old tradition of bottling in bond, but what brought this century-old practice back into the forefront?

Fly back in time to the late 19th century, when the whiskey market was more unregulated than you could even imagine. A rivalry for the record books emerged between straight whiskey distillers and whiskey rectifiers. Rectifiers, much like Non-Distiller Producers today, purchased distillate from other sources; they then aged it (for dubious periods of time), potentially tinkered with the finished product by adding flavoring or coloring, and bottled it at varying proofs under names such as “Fine Old Bourbon”. While a number of rectifiers produced honest-to-goodness whiskey, producers of knockoff bourbon flooded the market with their cheap, easy-to-produce whiskey and made it extremely difficult for straight whiskey producers to gain a foothold, and even forced many into bankruptcy.

Straight bourbon producers would not go down without a fight, and in the 1890’s, they brought this issue up in the courts. Colonel E. H. Taylor, Jr. was one of these crusaders, a name you might recognize as the founder of the Old-Fashioned Copper (O.F.C.) distillery (and Buffalo Trace’s current distillery) and namesake of one of Buffalo Trace’s more desirable bottlings. Although he was forced to sell O.F.C. to George T. Stagg in 1878, Taylor dedicated the rest of his life to the production and protection of straight bourbon whiskey. In the 1890’s he joined forces with John G. Carlisle, Secretary of the Treasury at that time.

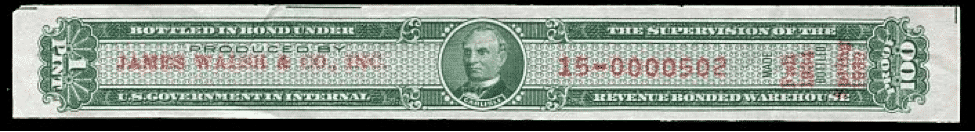

In order to ensure consumers of the quality of the whiskey they were purchasing, straight whiskey producers argued for a set of legal regulations regarding the bottling and advertising of bourbon whiskey. The practice of bonding warehouses had already been in place years before the 1897 Bottled-In-Bond Act came into existence, but the government had no role in what actually went into the bottle or onto the label. This act ensured that any whiskey bearing the name “Bottled-in-Bond” was produced by the same distiller, at the same distillery, during the same distilling season, aged for at least four years, unadulterated (save for pure water for dilution), and bottled at exactly 100 proof. The label also had to identify the distillery where the whiskey was distilled and bottled, and carried a green wrap over the cork featuring the mug of John G. Carlisle.

This act did not pass without a fight, though: whiskey rectifiers argued that this gave distillers an unfair advantage, and caused issues for rectifiers who were producing an honest product from the barrels and barrels of whiskey they bought and bottled. Isaac Wolfe Bernheim, founder of I. W. Harper and namesake of Bernheim Original Wheat Whiskey (Heaven Hill), fought vehemently against the passage of this legislation. He argued that the art of blending spirits was at risk because of the act, and allowed distillers to monopolize the whiskey market. Ultimately, he lost a footing in the debate and the act went through when President Grover Cleveland signed the bill into law on March 3, 1897.

The story was not over yet. Rectifiers and distillers crossed blades again during debates about the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act, which sought to remedy issues in the production and advertising of food and beverages. This act defined whiskey as straight whiskey, and all other products as imitations or compounds. A three-year battle ensued over the rights for other whiskeys to be labeled as such, not just straight whiskey. During this skirmish, straight whiskey producers even garnered the support of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, who supported straight whiskey since it was an all-natural product and, therefore, the lesser of two evils. Ultimately, President Taft made the final decision on how whiskey can be advertised in America, which was released in December of 1909.

As is true with many bourbon sagas, Prohibition and the popularity of clear alcohol stifled the bourbon market, and along with it, the prevalence of bonded bourbon. Now more than ever, bottled-in-bond bourbons can be found on the shelves of most Ye Olde Liquor Stores, but at what benefit to the consumer? We no longer have to worry about our bottle of liquid gold containing flavoring, coloring, or non-grain distillate. A number of additional federal regulations were put in place after the introduction of Bottling-in-Bond that protects the name of bourbon from foreign invaders, so why bother with antiquated guidelines? The tradition of Bottling-in-Bond exists today for the same reason as the Reinheitsgebot, also known as the German Beer Purity Law. It allows us to pay homage to our alcohol-making ancestors and the hard work they did to stand for what they believed in. So whether you kick back with a glass of E. H. Taylor, Old Forester 1897, or even Heaven Hill BIB, raise your glass to the crusaders who made possible the legislation that led to the bourbon we know and love today. Cheers!